- Reaction score

- 1,700

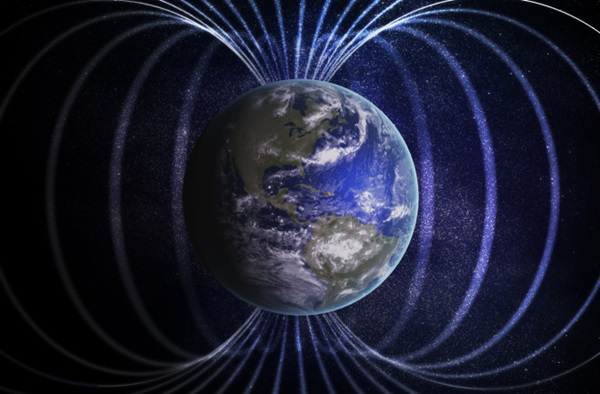

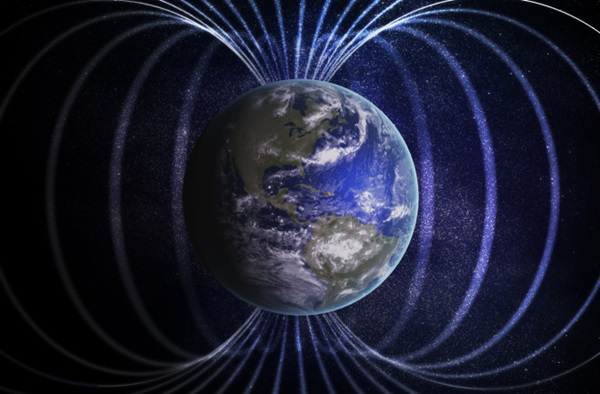

Something odd is happening to Earth’s magnetic field. Over the last 200 years, it’s been slowly weakening and shifting its magnetic north pole (where a compass points, not to be confused with the geographic north pole) from the Canadian Arctic toward Siberia. In recent decades, however, that slow shift south has quickened — reaching speeds upwards of 30 miles per year (48 kilometers per year). Could we be on the brink of a geomagnetic reversal, in which the magnetic north and south poles swap places?

Earth’s magnetic field is generated by the convection of molten iron in the planet’s core, around 1,800 miles (2896 km) beneath our feet. This superheated liquid generates electric currents that in turn produce electromagnetic fields. While the processes that drive pole reversal are comparatively less understood, computer simulations of planetary dynamics show that the reversals arise spontaneously. This is supported by observation of the Sun’s magnetic field, which reverses approximately every 11 years.

Our own magnetic field came into existence at least 4 billion years ago, and Earth’s magnetic poles have reversed many times since then. Over the last 2.6 million years alone, the magnetic field switched ten times — and, because the most recent occurred a whopping 780,000 years ago, some scientists believe we are overdue for another. But reversals are not predictable and are certainly not periodic.

Researchers map out the ancient history of Earth’s magnetic field using volcanic rocks. When lava cools, the iron that it contains is magnetized in the direction of the magnetic field. By examining these rocks and using radiometric dating techniques, it’s possible to reconstruct the past behavior of the planet’s magnetism as it strengthened, weakened or changed polarity.

To track more recent magnetic changes, scientists turn to the magnetic properties of archaeological artifacts. When our ancestors heated an ancient hearth or kiln containing iron to high enough temperatures, it would realign its magnetism with Earth’s magnetic field upon cooling. The point at which this occurs is known as the Curie point. Studies have even included some floor segments of an Iron Age building in Jerusalem, which a Babylonian army burnt down in 586 B.C.

But carrying out measurements on these archeological artifacts is difficult. For one, the magnetism in ancient objects is very weak — not enough to move a compass needle. And if any objects were heated and cooled several times, several magnetic patterns will be superimposed. Lastly, their reliability is dependent on the objects remaining in the same location that the heating took place.

Despite these difficulties, researchers have largely mapped modern changes in the magnetic field beneath western Europe and the Middle East.

astronomy.com

astronomy.com

Earth’s magnetic field is generated by the convection of molten iron in the planet’s core, around 1,800 miles (2896 km) beneath our feet. This superheated liquid generates electric currents that in turn produce electromagnetic fields. While the processes that drive pole reversal are comparatively less understood, computer simulations of planetary dynamics show that the reversals arise spontaneously. This is supported by observation of the Sun’s magnetic field, which reverses approximately every 11 years.

Our own magnetic field came into existence at least 4 billion years ago, and Earth’s magnetic poles have reversed many times since then. Over the last 2.6 million years alone, the magnetic field switched ten times — and, because the most recent occurred a whopping 780,000 years ago, some scientists believe we are overdue for another. But reversals are not predictable and are certainly not periodic.

Researchers map out the ancient history of Earth’s magnetic field using volcanic rocks. When lava cools, the iron that it contains is magnetized in the direction of the magnetic field. By examining these rocks and using radiometric dating techniques, it’s possible to reconstruct the past behavior of the planet’s magnetism as it strengthened, weakened or changed polarity.

To track more recent magnetic changes, scientists turn to the magnetic properties of archaeological artifacts. When our ancestors heated an ancient hearth or kiln containing iron to high enough temperatures, it would realign its magnetism with Earth’s magnetic field upon cooling. The point at which this occurs is known as the Curie point. Studies have even included some floor segments of an Iron Age building in Jerusalem, which a Babylonian army burnt down in 586 B.C.

But carrying out measurements on these archeological artifacts is difficult. For one, the magnetism in ancient objects is very weak — not enough to move a compass needle. And if any objects were heated and cooled several times, several magnetic patterns will be superimposed. Lastly, their reliability is dependent on the objects remaining in the same location that the heating took place.

Despite these difficulties, researchers have largely mapped modern changes in the magnetic field beneath western Europe and the Middle East.

When north goes south: Is Earth's magnetic field flipping?

It's been 780,000 years since this happened — and some scientists say that Earth's magnetic poles are long overdue for a switch.